By Ameera Steward

The Birmingham Times

The Southtown Court gymnasium on University Boulevard was filled with residents earlier this month, as Housing Authority of the Birmingham District (HABD) leaders held a conversation about the future.

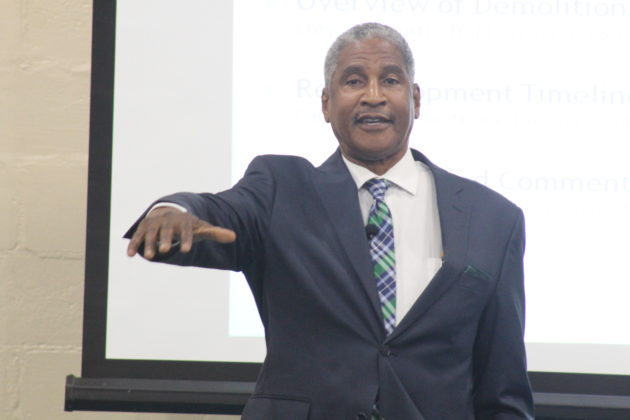

“I’m going to say to you, as president and CEO of the housing authority, that your best interest is in … our hearts,” Michael Lundy, head of HABD, told the residents. “We’re not going to do anything unless and until we have a conversation.”

For the next two hours, during a breakout session and an update from HABD’s partner Southside Development Co., Lundy and his executive team met with residents to discuss changes coming to the community.

The HABD’s plan, residents were told, is to demolish all the buildings—all 455 units, the management office, and the gym—and redevelop the area with upgraded, mixed-use housing and amenities; relocation options will be provided. Southtown Court is just one piece of a larger puzzle being constructed at HABD, one that involves nearly $100 million in total for renovations and capital improvements at 14 sites that stretch from one end of the city to the other.

“I know a lot of times the mayor [Randall Woodfin] talks about the 99 neighborhoods in Birmingham,” Lundy said. “We touch many of those neighborhoods in our public housing portfolio, so, as we transform those public housing communities, we’re helping to transform those 99 neighborhoods, as well.”

Cory Stallworth, HABD Vice President of Real Estate Development and Capital Improvement, said that transformation means improving in one way or another “all the developments we have.”

“We’re looking at each one of our sites and coming up with a strategic development plan to see how we can reposition our affordable housing,” he said. “A part of that is producing housing that does not look like public housing, that’s not cookie cutter, but is equal and equivalent to market-rate housing.”

The HABD has 4,737 public housing units and serves approximately 9,500 individuals.

Capital Plan

Work is ongoing at more than a dozen HABD sites.

“We have approximately 5,000 units and 14 sites, and we are putting together plans for all 14 sites,” said Stallworth. “[For] a few sites, we’re probably going to do very little. In terms of major redevelopment, there are at least seven [sites],” which will include approximately 2,500 units.”

In addition to proposed changes at Southtown Court, the HABD is doing major work at Loveman Village in North Titusville, where Phase 1 is underway and involves 100 units in different stages of construction; this effort will be complete by the fall. At Tom Brown Village in North Avondale plans include the demolition of certain portions of the property to make way for a new mixed-income, mixed-use community. At Morton Simpson Homes in Kingston, existing units will undergo interior and exterior renovations. Following the acquisition of Farrington Apartments in the Center Point community, property upgrades will begin after the transaction closes.

And just last week, the HABD began putting barriers on 12 streets in Marks Village to reduce the number of entry and exit points at the site to help reduce crime and started demolishing 204 units off the front end of the property along Georgia Road.

“We’re doing some other interesting things that are not necessarily public housing but are sort of a branch or offshoot,” Lundy said. “For example, we’re looking to acquire some single-family housing units that we can sell to families who are at 80 percent and below the area income.

“That doesn’t necessarily mean it’s going to always be somebody living in public housing; it could be somebody living across the street who is interested in home ownership,” he said. “When we do something good for the housing authority, we’re doing something good for the city of Birmingham.”

Opportunities

Renovations at Southtown Court on Birmingham’s Southside might be the HABD’s most current and visible redevelopment.

Southtown Court, built in 1941, is an older development with poor site layout, outdated materials, aging infrastructure, and a lack of modern conveniences.

“We’re looking to create a mixed-use development … that will be made up of affordable housing, as well as market-rate housing [and] amenities,” said Stallworth. “We have plans to put a grocery store on site; a hotel that will support the [nearby] St. Vincent’s and University of Alabama at Birmingham [hospitals]; same-day medical facilities for [outpatient procedures]; even office space because Southtown is located in a commercial environment.”

He added that the goal goes beyond just improving where residents live. It also means, “providing our residents with opportunities for housing in higher-opportunity areas, [such as] more suburban [locales], where [residents] have higher incomes and better schools. We’re looking at all these different initiatives to plan our redevelopment.”

The HABD also is working with nonprofit organizations and other groups to help provide housing.

“We’re working with the Woodlawn Foundation, a nonprofit that’s doing major reposition of some of the properties in Woodlawn,” Lundy said. “We’re working with them to provide affordable-housing and home-ownership opportunities. … What we’re doing in housing is not confined to just public housing and the funding we get from public housing; it’s a broader view. As we continue to envision and implement the vision, it will transform the city of Birmingham.”