By Erin Harney

alabamanewscenter.com

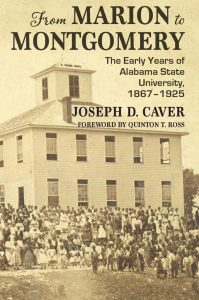

In the recently released “From Marion to Montgomery: The Early Years of Alabama State University, 1867-1925,” author Joseph Caver brings to light new information about the founding in a detailed history of one of the country’s earliest historically black universities.

Caver is a former senior archivist at the Air Force Historical Research Agency at Maxwell Air Force Base in Montgomery, a history lecturer at Alabama State University (ASU) and he was the first Black archivist at the Alabama Department of Archives and History.

Caver’s interest in researching his alma mater began during graduate school, while working at the state archives.

“I was working with all types of scholars using the resources there,” Caver said. While assisting an Auburn University graduate student researching Perry County history, Caver was told, “they’ve got it all wrong over there. … The school was founded much earlier than 1874.”

Intrigued, Caver delved into the microfilm collection of the American Missionary Association (AMA) papers, as well as newspapers and other primary source materials housed at the state archives – eventually developing his curiosity into a master’s thesis for graduate school.

Intrigued, Caver delved into the microfilm collection of the American Missionary Association (AMA) papers, as well as newspapers and other primary source materials housed at the state archives – eventually developing his curiosity into a master’s thesis for graduate school.

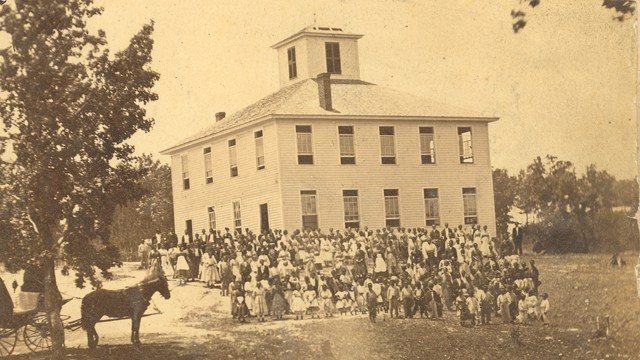

In his thesis, Caver provided evidence that ASU had been founded by freed slaves several years earlier than had been previously recognized.

“In the AMA papers, I found the incorporation of the Lincoln School on July 18, 1867. … I also went to the courthouse in Perry County and there was a reference there,” Caver said. “Using legislative records, I discovered the Lincoln Normal School received state funding in 1869, making it one of the country’s first state-supported educational institutions for Blacks.”

The Lincoln School’s incorporation papers were signed by nine members of the Black community in Marion who served as “elected” trustees for the school: James Childs, Alexander Curtis, Thomas Speed, Nickolas Dale, Thomas Lee, John Freeman, Ivey Parrish, Nathan Levert and David Harris.

Before Caver’s 1982 thesis, the university had celebrated 1874 as its founding and William Burns Paterson as its founder. Paterson, a native of Scotland and founder of the Tullibody Academy for Blacks in Greensboro, accepted the presidency of the Lincoln Normal School in Marion in 1878. His Feb. 9 birthday was designated as the university’s Founders Day in 1901.

“While Paterson wasn’t the founder, he was a great man,” Caver said. “He went against the grain when he didn’t have to.” Paterson was an advocate of the liberal arts and under his leadership the school experienced tremendous growth.

“The Marion Nine figured out that the way to improve the race was through education, and their establishment of a school was spectacular,” Caver said. “It testifies to the zeal that the half-million newly freed former slaves wanted to be educated.”

These new discoveries created some initial pushback.

“It was new research,” Caver said. “It’s history. … You uncover new things and basically try to find the truth.”

In 2017, Randall Williams, editor-in-chief of NewSouth Books, reached out to then-retired Caver about expanding his thesis into a complete history of the founding and early years of the university.

“Using the original thesis as the base, I uncovered so much additional information from the electronic records that are now available,” Caver said. “I could really go in-depth and bring those nine former slaves to life.”

“From Marion to Montgomery” provides extensive details, excerpts from the research materials, illustrations and photographs to provide a thorough history of the university’s first 60 years.

“I wanted the primary source documents to speak,” Caver said. “We get into this period of presentism, where we judge everything that occurs in 1867 by today’s standards. … I left that to the reader.”

For Caver, researching the story of African American education in Alabama had meaning because of the limited opportunities that were available to his father and grandfather.

“My grandfather was born in 1878 and he was able to go through the third grade at his community school and then he had to go to work,” Caver said. “My dad went through the eighth grade and then he was old enough to go to work in the agrarian community in rural Autauga County. … The availability of a higher education was limited to black Alabamians.

“In Alabama, we’re talking about a century of basically controlling what could be taught, how long you went to school, and what type of education you got,” Caver said.

By founding the Lincoln School, the newly freed black residents of Marion made an impact on generations to come. Historian and social researcher Horace Mann Bond studied African American education in Alabama. He discovered that the Black Belt region, because of the Lincoln Normal School and its successors, produced a disproportionately larger number of Black doctorate recipients.

The school flourished in Marion until 1886, when an altercation between white cadets from Howard College and black students from the Normal School occurred. The following week, a petition to relocate the Normal School began circulating.

The school was relocated in 1887 to Montgomery when the state Legislature decided to establish the Colored People’s University. Many among the city’s white community were against the relocation and shortly thereafter, according to Caver, a lawsuit led to defunding the university.

“For three years, the university went without funding,” Caver said. “But like the Marion Nine and the community in Marion, the Black community in Montgomery came together. … Members of the Black community purchased a 5-acre plot of land, and the school got off to a rocky start.

“Mary Frances Terrell, a former student and long-time faculty of the university, called this period a time to pray and pay,” Caver said.

State funding was resumed in 1890 and President Paterson continued a liberal arts trajectory for the school. However, Jim Crow laws outlined in the 1901 Alabama Constitution affected the university, as those segregation laws did for the rest of Montgomery.

“The role that Alabama State plays in the (1955-1956) bus boycott is significant because of the struggles and challenges the institution went through from its inception through the Jim Crow era. The Montgomery streetcar boycott (1900-1906) paved the way for the launching of the Montgomery bus boycott,” Caver said. “It’s an unbelievable story – mentioned in the epilogue. … I took this work up to 1925 and decided much more research was needed to complete the story. Hopefully, current and future scholars will continue this work.”

In 1915, following Paterson’s death, John William Beverly, an African American, was named president of Alabama State. Born in Hale County, Beverly attended Tullibody Academy and the Lincoln School in Marion, followed by Brown University, where he received a bachelor’s degree in philosophy. Beverly returned to Alabama as assistant principal at the Lincoln Normal School in 1894.

“Things changed. … Beverly established the laboratory high school, which was a college preparatory school for Blacks,” Caver said. “Before 1900, to obtain a secondary education, Blacks had to attend one of the three Black normal schools. There were no public secondary education schools for Blacks until 1900. Today’s Black colleges did not achieve post-secondary status until 1920.”

The State Normal School (Lincoln) became a junior college in 1920 and a four-year institution in 1927. Over the decades, the school continued to develop, from the State Teachers College and Alabama State College for Negroes, to Alabama State College, and finally became Alabama State University in 1969.

“This is what my work has uncovered,” Caver said. “Some of the misconception that we call colleges who were really just normal schools but that was as high and as far as they could go unless they went out of state.”

Caver said he’s extremely proud of his work.

“My journey as a historian and archivist has been quite rewarding. I enjoy sharing information with other people; that’s my calling,” he said. “That’s why I was an archivist for all those years … and because I’m an African American, I migrated to this study to tell the story of this distinguished black university.”

“From Marion to Montgomery” is available through local and online booksellers. For more information, visit: www.newsouthbooks.com/frommariontomontgomery.