Matt Windsor

UAB Reporter

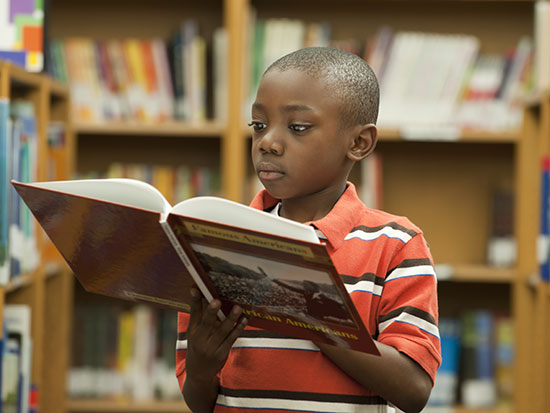

In every life are moments that can be pivotal. But few may be more consequential, or overlooked, than the third-grade reading test.

As School of Medicine Dean Selwyn Vickers, M.D., explained during the school’s COVID-19 Research Symposium in October 2020, education is seen as the “great equalizer” in America. But by the end of the third grade, a large proportion of America’s children are already far behind, with little hope of catching up.

‘13 times less likely to graduate’

“If you are a child who does not read at the third-grade level by the third grade and you are poor you are 13 times less likely to graduate” from high school than your proficient, wealthier peers, Vickers said, citing a landmark 2011 paper by sociologist Donald Hernandez, Ph.D. Individuals who do not graduate from high school have lower life expectancies, higher risk of chronic diseases and a higher likelihood of encountering law enforcement and prison than their counterparts who do graduate, Vickers added.

The problem is particularly acute for African American students, he continued. A study of 26,000 students in Chicago found that 44% of African American males read below third-grade level, compared with 18% of white males, Vickers said. Eighty percent of students who were reading below grade level in third grade did not attend college. By contrast, only 25% of students who were reading at or above grade level did not attend college.

Reading on grade level “clearly affects the health care you might experience in your life,” Vickers said. It also affects your “opportunity for college, employment and income and avoiding some of the health disparities we see” — in particular, in the context of this presentation, the documented disparities in COVID-19 outcomes, he said. COVID-19 has infected and killed Black Americans at a disproportionately high rate. For example, during the height of COVID infections in Milwaukee County, Wisconsin, African Americans accounted for 73% of deaths from COVID-19 even though they make up only 26% of the population. In Chicago, African Americans account for 32% of the population but 67% of deaths; for the state of Illinois as a whole, those figures are 14% of the population and 42% of deaths.

As Vickers noted in his presentation, reading is just one of several factors, including economic disparities, health coverage, access to support systems and healthy food options, that all play a role. Addressing all of these problems will require a mix of immediate and long-term policy solutions, Vickers said.

One way to help make a difference

Reading is one area in which individual volunteers have the power to make a major difference in the lives of students. STAIR of Birmingham, a longtime community partner of UAB, pairs volunteer tutors one-on-one with students in Birmingham City Schools. (STAIR stands for Start the Adventure in Reading.) The tutors and students meet after school for an hour, progressing through STAIR’s proven curriculum and spending time reading popular books together, helping students develop a lasting love of reading.

Statewide in 2019, 52% of Alabama third graders were proficient in reading. In Birmingham schools, that figure was 23.7%. But during the 2018-19 school year, the 231 students who participated in STAIR tutoring achieved an average reading score improvement of 103% and performed 30% better on annual assessments of reading than their peers who did not take part.

Students often tell their teachers that “STAIR day” is their favorite day of the week, says Karen Griner, chief executive officer of STAIR of Birmingham. After schools closed at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in spring 2020, STAIR quickly transitioned online and “by April we were back up and running with a virtual program,” Griner said. “We had 600 virtual tutoring sessions in the last two months of the school year and started a summer program for the first time.”

Based on “feedback over the summer from parents, we had a lot of students just as excited about STAIR day, even when it was remote,” Griner added. “Kids still enjoy the one-on-one interaction with their tutors.” STAIR already was planning to implement a revised curriculum prior to the pandemic, so “we adapted to write a curriculum that works really well in person, by video or even on the phone,” Griner said.

No teaching background needed

Tutors do not need to have a teaching background, Griner said. “Anyone who wants to participate can be paired with a student, and we do all the training. We even have scripts they can use until they get used to what a session is like; and if they are still apprehensive, we can do one-on-one support.”

UAB students and employees are an important source of STAIR tutors, Griner said. (Employees and students can sign up through UAB’s BlazerPulse website here.)

STAIR of Birmingham’s leadership team also has UAB connections: Tiffany Osborne, director of community engagement for UAB’s Minority Health and Health Disparities Research Center (MHRC), is a member of the group’s board of directors.

“The MHRC does a lot of work in the same communities where STAIR is embedded,” Osborne said. “We are in Kingston with Building Healthy Community coalitions, and some of our members in the coalition are also involved in STAIR. Much of our work in the MHRC is centered around educating individuals in those communities about physical activity, wellness and prevention. Those guiding principles of education align perfectly with what STAIR is helping to accomplish.”

Whether as a tutor or by contributing funds, Osborne said, “this is such a unique opportunity for faculty, staff and students at UAB to be involved in projects that reach under-served populations.”