LOS ANGELES (AP)

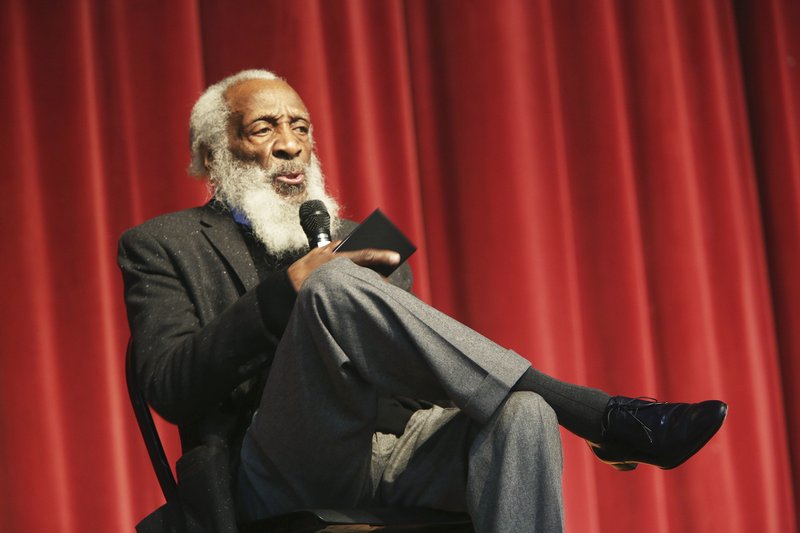

Dick Gregory, who broke racial barriers in the 1960s and used his humor to spread messages of social justice and nutritional health, has died. He was 84.

Gregory’s son, Christian, told The Associated Press his father died late Saturday in Washington, D.C. after being hospitalized for about a week. He had suffered a severe bacterial infection.

“It is with enormous sadness that the Gregory family confirms that their father, comedic legend and civil rights activist Mr. Dick Gregory departed this earth tonight in Washington, D.C.,” said a statement from Christian Gregory on the “therealdickgregory” Instagram page. “The family appreciates the outpouring of support and love and respectfully asks for their privacy as they grieve during this very difficult time.”

“He was one of the sweetest, smartest, most loving people one could ever know,” his publicist of 50 years, Steve Jaffe told The Hollywood Reporter. “I just hope that God is ready for some outrageously funny times.”

As news of Gregory’s death made its way into the news cycle, The Hollywood Reporter wrote that fellow celebrities were in mourning, as demonstrated by their Twitter feeds:

“Ava DuVernay shared a quote of Gregory’s, and captioned it, ‘You taught us and loved us. Thank you, #DickGregory.’

“John Legend, who produced the off-Broadway play Turn Me Loose — in which Emmy-winning actor Joe Morton (Scandal) portrayed Gregory — tweeted, ‘Dick Gregory lived an amazing, revolutionary life. A groundbreaker in comedy and a voice for justice. RIP.’

“Bill Cosby fired off several tweets, praising Gregory’s work, saying it showed “education, intelligence, and was inclusive of humanitarianism along with great timing’.”

Richard Claxton Gregory was one of the first black comedians to find mainstream success with white audiences in the early 1960s. He rose from an impoverished childhood in St. Louis to become a celebrated satirist who deftly commented upon racial divisions at the dawn of the civil rights movement.

The New York Times, one of many news outlets which documented Gregory’s rise to prominence, said that he had gotten his big break as a comic in January 1961 when he filled in at Chicago’s Playboy Club following a cancellation by comedian Irwin Corey. “On the big night, club managers had misgivings,” Clyde Haberman wrote in the Times. “The house was packed with businessmen from the Deep South. No matter, Mr. Gregory said. He insisted on performing.

“‘I understand there are a great many Southerners in the room tonight,’ he began his act. ‘I know the South very well. I spent 20 years there one night.’ He so won over the crowd that Playboy’s Hugh Hefner signed him for three more weeks, then extended the contract,” Haberman wrote.

The visionaryproject.org in introducing an oral history of Gregory said that he “put his convictions into practice by devoting much of his time to the civil rights movement of the 1960s. On behalf of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the Congress on Racial Equality, and other prominent civil rights organizations, Gregory made appearances at demonstrations, marches, and rallies throughout the country. He performed in many fundraising shows for the movement and participated in nonviolent civil disobedience actions.”

Some of those actions took place throughout the South, including in Selma and here in Birmingham during the pivotal years of the civil rights movement led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Bethel Baptist Church’s fiery pastor Fred Shuttlesworth.

The New York Times described how Gregory turned his talents and attention increasingly to civil rights:

In 1962, Mr. Gregory joined a demonstration for black voting rights in Mississippi. That was a beginning. He threw himself into social activism body and soul, viewing it as a higher calling.

Arrests came by the dozens. In a Birmingham, Ala., jail in 1963, he wrote, he endured “the first really good beating I ever had in my life.”

He added: “It was just body pain, though. The Negro has a callus growing on his soul, and it’s getting harder and harder to hurt him there.”

In 1965, he was shot in the leg (the wound was not grave) by a rioter as he tried to be a peacemaker during the Watts riots in Los Angeles.

Increasingly, he skipped club dates to march or to perform at benefits for civil rights groups. Club owners became reluctant to book him: Who knew if he might fly off to Alabama on a moment’s notice?

Turning to politics, Gregory ran for mayor of Chicago in 1966, and president in 1968 as the Peace and Freedom Party candidate. “Gregory’s campaigns were closely associated with the New Left and Black Power movements of the late 1960s and called for civil rights, peace in Vietnam, and racial and social justice,” according to visionaryproject.org. “Although neither of his electoral campaigns were successful, they did draw attention to issues that Gregory felt should be better known. His unsuccessful presidential bid, a write-in effort in most states, garnered some two hundred thousand votes and substantial media attention.” (The numbers on Gregory’s presidential bid vary according to which source reports them; The New York Times lists the official figure as just over 47 thousand).

Gregory became a vegetarian and an advocate for good nutrition, and as a way of drawing attention to various causes, he took to hunger strikes, sometimes for weeks. His interest in nutrition led Gregory to demonstrate particularly strong convictions about the power of good food. “In late 1999, he learned he had lymphoma but rejected chemotherapy, relying instead on vitamins, herbs and exercise,” Haberman wrote in the Times. “The cancer went into remission.”

In the late 1950s, Gregory met and married Lillian Smith. Together they had 11 children, one of whom died in infancy.

Gregory, who continued to perform comedy and write, also continued his social activism. In 2014, he spoke at the Ferguson and Beyond demonstration at the U.S. Department of Justice in Washington, D.C, and the following year at the “Shut it Down for Mike Brown” one year rally at the African American Civil War Memorial in D.C. Gregory also spent some time on social media. Recently, on Instagram, he was promoting his upcoming book, Defining Moments in Black History: Reading Between the Lies.

In an Instagram post Sunday morning, Christian Gregory paid a touching tribute to his dad:

A healthy dose of wit and wisdom just arrived in heaven, of that I am absolutely certain.

Dick Gregory is eternal. He sacrificed so others could, the true beauty was that the others were always the disenfranchised and the underdog. There is a profound amount of ugly in the world today. Consider some slight discomfort to make life a little better as we pay tribute to a lifelong crusader.

I miss you already Pop. You were undoubtedly a fine human being and the coolest Dad! It was a pleasure and an honor being your wingman!

Loving and lovable,

Christian