By Barnett Wright

The Birmingham Times

When Autumm Jeter, EdD, was named superintendent of Bessemer City Schools in early 2020, she learned of a potential partnership that would bring prime benefits for students and faculty.

Amazon, now the city’s largest employer, wanted to find ways to collaborate with the school system—and the tech giant followed through.

“The relationship has blossomed,” Jeter said. “They were here before I was hired, and they gave me time to get on the job before they reached out to us. They were adamant about developing a relationship with the local school system.”

Two months ago, Amazon donated $15,000 to Bessemer City Schools, Jeter said. Also, when the water fountains were being repaired in school buildings, the tech giant provided bottled water for the facilities, offices, and children, said the superintendent.

This month marks one year since the Amazon Fulfillment Center opened in Bessemer, Alabama, transforming not only the Marvel City but also the region. According to interviews, Amazon’s opening has lifted the education system, as well as area businesses and housing.

“Having [Amazon] has had a great impact on the city of Bessemer,” said Tasha Cook-Williams, president of the Bessemer Chamber of Commerce. “It helps to boost growth all the way around. Donating to the education system allows the schools to provide more resources for the children. … Also, not everybody wants to go for a college education, [and Amazon] has created great avenues and opportunities for students who are in high school to make [decent] wages.”

Bessemer Mayor Ken Gulley called Amazon’s presence a “game changer.”

“When you get a world-renowned company such as Amazon in your city, it pays major dividends in more than one way,” he said. “Obviously, it pays when you employ over 5,000 residents not only in Bessemer but in Jefferson and surrounding counties. … It also makes the recruiting of other businesses obviously easier.”

Gulley pointed to the city’s recent economic growth, which includes the addition of online used car retailer Carvana, known for its multistory automobile vending machines; the Lowe’s Distribution Center, a 1.2-million-square-foot facility; another Amazon Delivery Center; and a FedEx Distribution Center.

Ofori Agboka, an Amazon vice president, said the $320 million facility in Bessemer, which officially welcomed new employees on March 29, 2020, for the first day of operation, is focused “not just on jobs but careers.”

“We’ve invested in individuals and their families and the community, as well,” he said. “We have so [many] opportunities to partner with the school district. … We’re excited about what we can do with our engineering program and our mentoring programs, in addition to helping youngsters see that a broad range of careers are available after high school.”

Union Battle

The past year for Amazon in Bessemer has been notable for another reason, too: The center has become ground zero for unionization efforts that have garnered international attention.

Employees at the center, where workers dispatch orders for the online retailer, are voting whether to join the Retail, Wholesale, and Department Store Union (RWDSU). With a membership of up to 18,000 members in Alabama, the RWDSU represents more than 100,000 individuals across the U.S., encompassing grocery store employees, soda bottlers, sanitation and highway laborers, and, in the South, poultry workers. Ballots for a mail-in vote were sent to more than 5,000 on Feb. 8; workers must return them by March 29.

The moment has attracted the attention of the National Football League (NFL) Players Union, the Biden-Harris Administration, actor Danny Glover, Democratic strategist Stacey Abrams, and a contingent of U.S. House of Representative Democrats, all of whom are in favor of the union. The vote could spell a new era not only for unions but for one of the world’s most successful corporations.

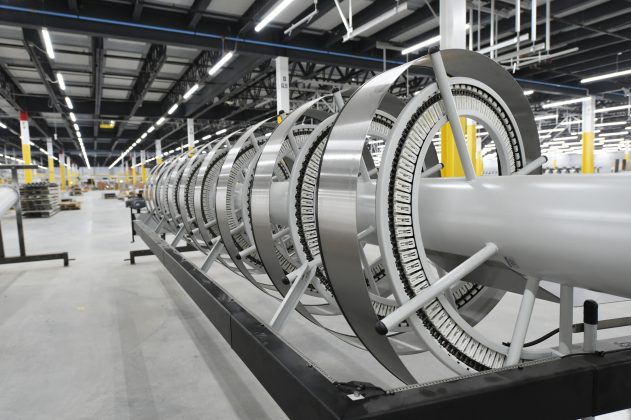

The Amazon Fulfillment Center is a large repository of goods, where employees, working among robots and conveyor belts, sort through an array of items to satisfy up to 100,000 Amazon orders a day.

Many of the employees at the Bessemer facility are Black. Seventy-one percent of Bessemer residents are Black, and 28 percent of the city is classified as poor, according to census figures.

Max Gleber, a spokesman for Amazon, has said the company believes the union does not represent the majority of its employees’ views, and that its total compensation package, health benefits, and workplace environment compare favorably with other companies offering similar jobs.

“We opened this site in March [2020], and since that time have created more than 5,000 full-time jobs in Bessemer with starting pay of $15.30 per hour, including full health care, vision, and dental insurance and a 50 percent 401(k) match from the first day on the job in a safe, innovative, inclusive environment with training, continuing education, and long-term career growth,” Gleber said.

Anti-Union

Carrington Byers of Ashville, Alabama, is one of the more than 5,000 employees who received a ballot last month and already voted no on the union, he told AL.com. He works in outbound problem-solving, an atmosphere he simultaneously calls “very strict” and “very relaxed,” and said his experience at Amazon has been positive. In his opinion, it’s the best job he’s ever had.

“For me, it’s been a fact of, this is the first really big job that I’ve had where I’ve made this amount of money,” Byers said. “The benefits I’ve seen is like, they’ve been good. I’ve never been at a place with really good benefits. I’ve been looking at all the good things.”

Dawn Hoag, 43, said she will not vote for union representation at Amazon. Hoag works in inventory control and quality assurance, which means she is involved with training and performance issues at the company’s four-story, 855,000-square-foot center.

“I have yet to encounter anyone personally that is pro-union,” Hoag said. “Unless someone is straight lying to my face, which I don’t believe. Nobody I interact with has ever told me that they are pro-union. I 1,000 percent believe everyone has a right to feel whatever they want. If I did encounter someone that way, I wouldn’t treat them any differently. The only question I would pose is to ask what avenues they have exhausted that made them feel this is the way to go.”

Pro-Union

Union organizers stress that the issues they’re arguing about now could become much larger in years to come. Stuart Appelbaum, RWDSU president, said the importance of this election transcends this one facility and even Amazon itself. With the rapid acceleration of technology in the workplace, Applebaum’s concerns include an environment in which workers receive assignments from robots and are disciplined through phone apps, even sometimes fired by text, with little opportunity to argue their case as individuals.

“Amazon is transforming industry after industry, and its model will help determine what the future of work looks like,” he said.

Jennifer Bates, 48, who lives in Birmingham, said she started at Amazon in May 2020, after holding a variety of jobs, including holding positions in the steel and automotive industries and working as an administrative assistant. She had previously been a member of unions at those workplaces.

What’s missing at Amazon, Bates said, is a sense of commitment from management to employees. She added that frequent complaints among workers revolve around issues like the demands of the job, work times, and a general lack of communication. Some of these issues by themselves might not stand out as much as they do collectively. An employee working a 10-hour shift, for instance, has two 30-minute breaks, she said. If that employee works on the fourth floor, it takes time to get to break areas around the massive center.

Employees also have to manage long hours on their feet, going up and down stairs and navigating the large distances without losing worktime. Workers are encouraged to bring food that doesn’t need to be heated up, in order to save time. If they’re being encouraged to work more time, Bates said, an extra 15-minute break might make things easier.

Add to that the occasional confusion over when someone is expected to work. Bates said she was once told to check her employee app for her work hours the following week to be alert to possible mandatory overtime. She did, and she saw none. When she got to work on Monday, however, she discovered that she had been scheduled to start an hour earlier, and the time came out of her paid time off. She made up the time by staying late.

Bates said she isn’t the only person this has happened to: “Some people lost a whole day. Some got their time back. Some didn’t. They basically put the problem on the employees. If you run out of unpaid time, you’re out the door. … Amazon could be an awesome place to work. We do this because we love it. But we don’t get the same commitment.”

Darryl Richardson of Tuscaloosa, Alabama, works as a picker—filling orders and maintaining stock levels—and has been on the job practically since the facility opened. He said talk of the union gained steam last year, with employees concerned about several issues, including COVID-19 procedures, overtime, and how responsive management was to employee needs.

“If we get this union, we can get some of this turned around,” he said.

City Expects More

Regardless of the union vote, one thing will not change: Amazon’s place in the community—and some are expecting the tech giant to do even more.

“I know they have been here only a year, and it’s been an abbreviated year because of the pandemic,” said Mayor Gulley. “I want them to be more even involved in the school system. … I would like to see them support our first responders, our policemen and firemen. I’d like to see Amazon more involved in our recreation center and our young people and sponsor some of our equipment [to] offset some of those costs [for] our parents.”

Nikki Forman, an Amazon spokesperson, said the company is looking forward to establishing “meaningful, lasting, sustainable relationships” in Bessemer.

“You’ll see Amazon’s footprint across a variety of different organizations, from the Boy Scouts to hospitals to volunteering charity events to local churches,” Forman said. “[The] Amazon Future Engineers program is going [to have an] impact on students in the Bessemer City Schools system, and we’ve also started conversations looking outside of Bessemer as we continue to be a part of the fabric of greater metro Birmingham. … You will see Amazon in a major way threaded throughout this community.”

Gulley said he hopes so.

“I’m looking for a long-term partnership. This has been a marriage I’m looking to sustain for a long period of time … for the good of Bessemer and the whole western side of Jefferson County,” he said.

AL.com contributed to this article.