By Ameera Steward

For the Birmingham Times

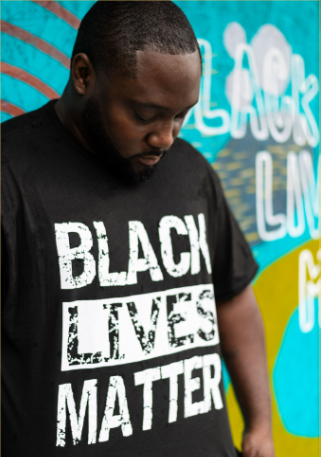

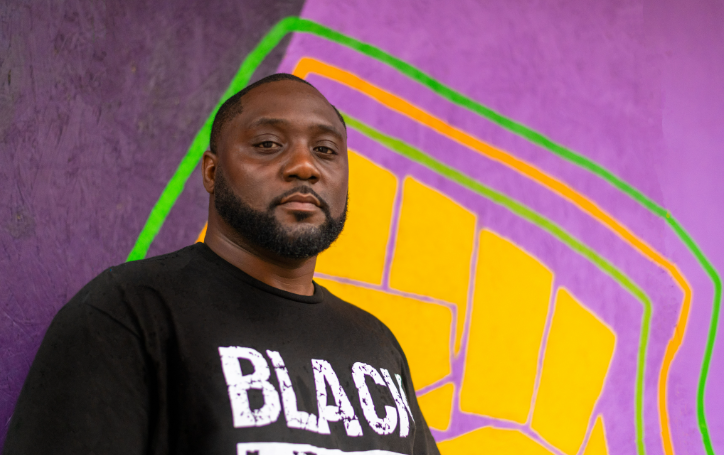

Activist Eric Hall grew up in two cities with names that make people think of Black lives.

The 38-year-old is originally from Flint, Michigan, a town known nationally for not providing clean drinking water to its mostly African American population. At age 9, he moved from there to Birmingham, a city with a name synonymous with the Civil Rights Movement.

“If I can do something today that will make life better for people tomorrow, then I feel like I will have accomplished what I was meant to do,” Hall said. “So, I live life each day to make a difference for not just me but for others … that have better days ahead. … I just uplift all of my ancestors who have died. Their blood lays in the street, … so I just want to honor their legacy, to honor their names, to fight.”

Hall is a co-founder of Black Lives Matter (BLM) Birmingham, the local chapter of a movement dedicated to advocating for nonviolent civil disobedience in protest against injustices toward African American people; he was recruited by Cara McClure, who was familiar with some of his activism.

“I’ve been part of BLM [since 2016], before the water crisis [in Flint], but that is a reason why I fight,” Hall said. “Issues like that … encourage and inspire my activism.”

Giant Footsteps

Hall has always identified himself as a helper. His mentor, the late Dr. Arthur J. Pointer, was a strong community-oriented pastor in Flint and an inspiration for the young Hall.

“I didn’t realize until much later the impact the Rev. Pointer had on my life,” Hall said. “As a child, I admired him, so my dream job was to be a preacher.”

In the early 1980s, Flint was one of the poorest communities in the nation. Hall said he and his peers glorified gangs and gangster rap music and went as far as to form a community gang—but the Rev. Pointer, along with community elders and family members, broke up the gang and connected the boys with a mentoring group.

“In my later years, I found out how politically connected he was and his involvement with forming an AIDS outreach program in the church,” Hall remembered. “I would say this, I’m following the footsteps of a giant. I’m a preacher, I’m politically strong, and I’ve worked to combat [human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)] and AIDS. The sky is the limit. Through serving God first and community, all things are possible.”

Hall himself has been a minister since 2000 at Peace Missionary Baptist Church in the Pratt City neighborhood. It was divine inspiration, he said.

“Through my involvement with church, through building a relationship with Christ, I discovered that I had a unique calling on my life, and I followed that calling,” he said.

Along with Rev. Pointer as a role model, Hall also points to his mother, Rosetta Hall.

“She is the epitome of a servant leader,” he said. “She had an incomparable work ethic and love for [her] community.

“My mother sacrificed to provide for her children. It’s from her that I learned my work ethic, … [as well as] how to be resilient.”

Hall’s mother worked entire adult life for minimum wage. In the early 1990s, she earned approximately $4 an hour; when she retired around 2011, she got up to $7.15 or $7.25 an hour.

“She literally only earned a dollar increase for every 10 years that she worked,” Hall said. “Those are some of the changes we have to begin to look at … and begin to address.”

“A Scary Time”

When Hall was 9 years old, his mother moved the family of five (he has three brothers and one sister) back to her hometown of Birmingham. That was in 1991.

“It was really a scary time, now that I think about it,” Hall said. “I think about all the horrible policing practices [I witnessed] as a child, and that’s what I really see in my head—images of what we called the ‘Jump Out Boys,’ … [police] literally going after every male figure in my community; even if guys were just standing outside, hanging out, [they] seemed suspect. The bad memory just stuck in my head.”

Those experiences skewed Hall’s perspective of police officers, he acknowledged, adding that he’s always been fearful of the police. Like many young black men in the community, Hall ran at the sight of the police.

“I honestly was terrified of the police,” he said. “That’s a common trigger a lot of people have, even when they get older. If someone is driving and the police get behind [them], … the person automatically just gets really nervous and jittery.”

A lot of that fear came back approximately three or four years ago, when the Birmingham Violence Reduction Initiative (BVRI) started. Hall was driving in his community of Pratt City, when he saw alarmed residents watch camouflage-clad police officers in army-style vehicles raid a street without warning. BLM met with community members and elected officials who represented the area.

“It was an opportunity for those in elected positions to hear the voices and concerns of the community,” he said.

Community Work

Hall’s community work goes beyond racial injustice. In 2006, he started street outreach with Jefferson County AIDS in Minorities Inc., an HIV and AIDS service organization.

“That was the first job where I was responsible for providing community education to the homeless population and to underserved and underdeveloped communities throughout the Birmingham metropolitan area,” Hall said.

In 2011, he was also responsible for helping individuals find housing and rebuild their lives after the devastating tornadoes that struck the area that year. Hall was concerned about the way federal and state dollars were being spent in the aftermath and decided in 2013 to run for the Birmingham City Council District 9 seat.

“I was very new in politics, … so I didn’t know how to fundraise, didn’t know how to really do a lot of things. I just knew I had a passion for it and wanted to see something change,” he said.

Hall finished third in the race—but remembers as “a year of change” for him.

“After canvassing District 9 and hearing from residents it was clear that residents wanted a representative compassionate about their concerns also educated enough to understand government, legislative processes and policies.”

He decided to enroll at Miles College who educated a long list of notable Birmingham leaders included the Honorable UW Clemon and former mayors Richard Arrington, Bernard Kincaid and William Bell. “Miles College has a rich legacy of social activism and continues to be on the forefront of fighting for social justice and equity,” said Hall, who graduated with a bachelor’s degree in political science in 2018 and is now a graduate student studying social work at Alabama Agriculture and Mechanical University.

As for politics, Hall plans to run for City Council again in 2021.

“It’s not about me,” he said. “I’m running because … I envision a Birmingham that can really be beautiful out of all of the [systemic injustice, racial inequities, and inequitable communities and services]. … We can change policies, we can change systems so they are more inclusive and not exclusive, so those systems can work for all people.

“I see an opportunity for a change, and I believe it’s possible that we can build off this momentum to make that happen.”

BLM Birmingham

In 2016, Hall was recruited for the BLM Birmingham chapter by Cara McClure, a member of the original local chapter.

“At the time, I just wanted to be part of an organization that … I deemed to be relevant in this moment,” Hall said, adding that he didn’t imagine having to continue the work for so long.

“After the killings of Trayvon Martin, [an unarmed 17-year-old shot and killed by a neighborhood watchman in Sanford, Florida], and Tamir Rice, [a 12-year-old carrying a toy gun who was shot and killed by a police officer in Cleveland, Ohio], I thought that by now, at this point, years later, we would have come up with a system that works, that we wouldn’t be dealing with continuous police shootings, that we would call for policy change and maybe get those wins, and that was probably going to be it,” he said.

“Unfortunately, Black [people] kept being killed by police. Even though we would take moments or breaks, as soon as it would happen again, we would find ourselves being called to the forefront to address these issues all over again.”

So many of the demands and recommendations activists are making now are the same ones made when Martin was killed, Hall said: “We’ve grown tired, so we’re a little more aggressive now than we were these past years. We’re really pushing now.”

“I see with this movement that young people are literally leading,” he said. “A lot of our youth are on the front lines; children are now engaged and involved. … [Young people] want immediate change, so I’m excited about the rebirth of this movement.”

As former president of the Central Pratt Neighborhood Association, many of Hall’s concerns deal with communities.

“My thing is we need to find a way to return power back to the people and allow the people to have a stronger voice in policies as it relates to their city,” said Hall, who is dedicated seeing that change is made beyond Birmingham, too. “[Alabama should be] somewhere we all can live and also thrive. We’re not fighting for equality but equity. Until we see that, my commitment is going to be to [make] sure that the policies reflect that Black Lives Matter.”

Updated at 1:44 p.m. on 7/15/2020 to correct Hall’s age.