By James L. Baggett

The stain of slavery, America’s original sin, runs through our history and culture. And the blight of racism remains with us, despite all efforts to pretend otherwise or wish it away. On race, historians play a vital role in helping us look back and move forward—and three recent books expand our understanding of this past and help reclaim the stories of enslaved people.

Americans are familiar with the Underground Railroad, a loosely connected series of safe houses and sympathetic individuals used by enslaved African Americans to flee to the northern United States and Canada. But University of Southern California historian Alice L. Baumgartner explores a different route for enslaved people seeking freedom—or something closer to freedom—in “South to Freedom: Runaway Slaves to Mexico and the Road to the Civil War” (Basic Books, 2020).

Enslaved people who fled to Mexico tended to come from Texas and Louisiana (walking more than 1,000 miles north was not a viable option for them). While there were people along the southern route who could help them, if the person running away happened to stumble upon such help, Black people fleeing south had to mostly rely on their own ingenuity.

“They forged slave passes” and “disguised themselves as white men,” Baumgartner writes. Some runaways “stole horses” for transportation and took valuables from their enslavers to finance the journey. The author estimates that 3,000 to 5,000 African Americans fled to Mexico, far fewer than the number of those who fled north, but that is not an insignificant number of people. By fleeing, these people had an impact on American policy toward Mexico and, Baumgartner argues, helped bring about the American Civil War.

Amy Murrell Taylor, who teaches history at the University of Kentucky, writes about African Americans who took a different route out of slavery in “Embattled Freedom: Journeys  through the Civil War’s Slave Refugee Camps” (University of North Carolina Press, 2018). Like the enslaved Americans who fled to Mexico, enslaved people throughout the Confederacy recognized that, as Taylor writes, “if freedom was to come during the Civil War, it was not going to come directly to them. Freedom had to be searched for and found.”

through the Civil War’s Slave Refugee Camps” (University of North Carolina Press, 2018). Like the enslaved Americans who fled to Mexico, enslaved people throughout the Confederacy recognized that, as Taylor writes, “if freedom was to come during the Civil War, it was not going to come directly to them. Freedom had to be searched for and found.”

Just days after the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, African Americans began fleeing their enslavers and seeking refuge with the U.S. military. At first, the Army turned escaped people away, but Black people kept arriving in larger and larger numbers and demanding their freedom. Soon military leaders recognized that sending Black people back to slavery helped the Confederate cause and denied the U.S. military a source of labor. Thousands of Black Americans escaped, and they created communities in the refugee camps that grew around U.S. military installations and in mobile camps that followed the U.S. Army as it moved.

As formerly enslaved people shared space and resources with their military protectors, they did not wait to begin new lives outside of slavery. In Virginia, husband and wife Edward and Emma Whitehurst opened a store selling potatoes, pork, and ginger cakes to their fellow refugees and U.S. soldiers.

In refugee camps across the South, Black people formed their own churches, sometimes telling white denominational leaders that their help was not needed. Black men joined the U.S. Army, knowing that securing freedom meant defeating the Confederacy. “Embattled Freedom” reminds us—because we still need reminding—that our Civil War was a war to end slavery. People who say otherwise are trading in racist mythology.

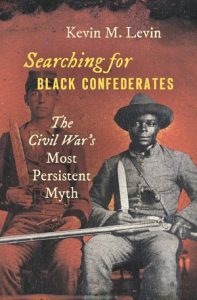

Kevin M. Levin dismantles more racist mythology in “Searching for Black Confederates: The Civil War’s Most Persistent Myth” (University of North Carolina Press, 2019). The myth of the Black Confederates, African American men who supposedly served in the Confederate military, dates from the 1970s and is still perpetuated today on websites, in books, and at museums and historic sites.

One piece of evidence that is commonly misinterpreted to make this argument is the photo featured on the cover of “Searching for Black Confederates.” Showing Andrew Chandler and Silas Chandler, the image is so popular among Confederate sympathizers that it is featured on websites and sold on T-shirts. But the photo does not show what sympathizers want it to show—a loyal Black man who fought alongside whites to defend the Confederacy.

Andrew was the son of a slave-holding family, and Silas was one of the people the family enslaved. Silas was not free, and he was not a Confederate soldier. Silas was a “camp slave,” taken to war by his enslaver to be a servant and laborer. And there were thousands more camp slaves, also not soldiers.

The myth of Black Confederates is popular and persistent because, if it were true, it might reinforce two pillars of Southern Lost Cause orthodoxy. Confederate sympathizers want us to believe that Black Americans were happy and content in bondage and that in the Antebellum South—that land of brutal beatings, family separations, and rape—everyone was just one big happy family. Confederate sympathizers also want the rest of us to believe that the Civil War had nothing to do with slavery. Neither argument is true. Both arguments are foolish.

“Civil War memory has always been a contested landscape,” Levin writes, and the contest was “never primarily about the past but rather about trying to make sense of the present.” And it was only weeks ago that an insurrectionist unfurled a Confederate flag inside the U.S. Capitol. These fights over the misuse of the past may always be with us. That is why books like “South to Freedom,” “Embattled Freedom,” and “Searching for Black Confederates” need to be widely read.

James L. Baggett is an archivist and historian in Birmingham, Alabama. He may be contacted at TalkToBaggett@gmail.com.

To read more stories about Black History, click one of the links below.