By Anita Debro

For the Birmingham Times

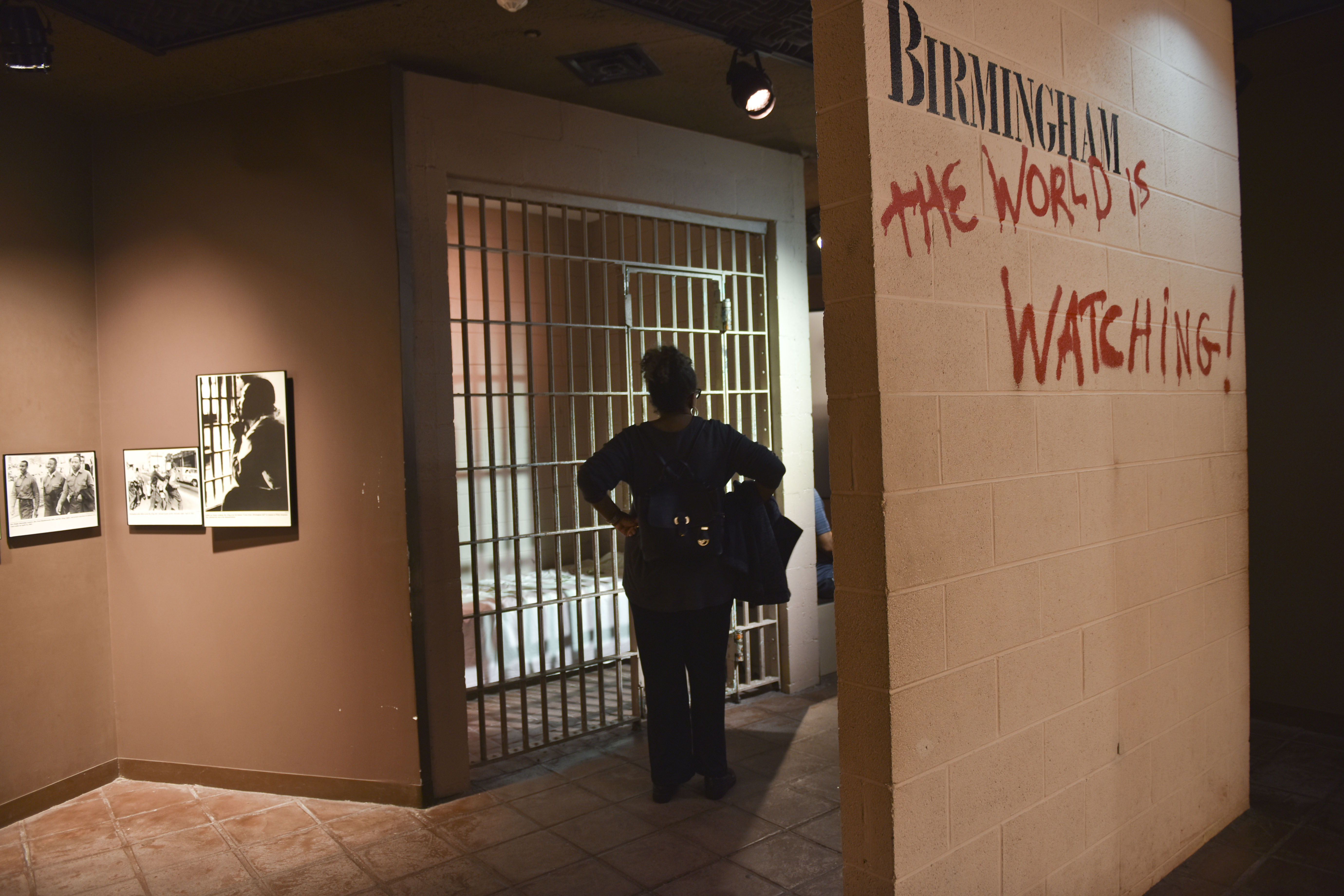

The dignified domed building on 16th Street North in downtown Birmingham looks as though it was always meant to be there. The Birmingham Civil Rights Institute (BCRI) is flanked by historic Sixteenth Street Baptist Church to the north and Kelly Ingram Park to the east. And this year, the BCRI is celebrating its 25th anniversary.

Former Birmingham Mayor Richard Arrington Jr. said establishment of the institute was a priority when he was first elected to office in 1979. He put together a 21-member task force that eventually led to the opening of the facility.

“It was very important to me that young people understand the history here,” said Arrington, Birmingham’s first African-American mayor, who is now a professor at Miles College. “It is easy to think that things have always been the way they are now, but what happened in Birmingham in the 1960s is not ancient history.”

The BCRI, which opened on Nov. 15, 1992, recalls a time in Birmingham’s history that many initially wanted to forget. Some were even opposed to the creation of the institute. Today, many recognize and laud the Institute for confronting the city’s past, shining a light on international civil rights issues, and honoring the foot soldiers who sacrificed to end segregation and help make Birmingham the city it is today.

More Important than Ever

Since its opening, more than two million visitors have visited the BCRI, and its role today is more important than ever.

“Almost everyone would agree that this is a very challenging and troubling time in our history,” said BRCI President and CEO Andrea Taylor. “We can play a very important role by providing a place where people can gain factual information and share dialogue; by providing a place where people have an opportunity to interact with different people by building coalitions; and by providing a place where people can continue to learn, share, and grow in an increasingly complex society.”

On Saturday, Nov. 18, the BCRI will mark its 25th anniversary during its annual Fred L. Shuttlesworth Human Rights Awards Dinner, where Arrington and activists Harry Belafonte and Viola Liuzzo, who is being honored posthumously, will be recognized.

Birth of the BCRI

Arrington has been a part of the BCRI since its planning stages, but he has always credited the idea to late Birmingham Mayor David Vann, who visited a Holocaust museum in Israel and returned to Birmingham with a mounting interest in establishing a civil rights museum. Vann lost his bid for re-election, but Arrington pledged that he would continue the commitment to build a museum dedicated to the individuals who gave their lives for equality.

Arrington tapped civic leader Odessa Woolfolk in 1986 to lead the institute’s task force, which had a goal of formulating the plans—from mission statement to content and design. Talent was recruited from the city’s education, arts, and business communities to work on the project.

“What happened here in Birmingham was transformative,” said Woolfolk, BCRI Founding Board Chair. “We wanted to tell the story of how a movement of nonviolence was used to resolve conflict.”

Woolfolk, who grew up in Titusville, was the ideal person to chair the task force. She was an educator who had public policy experience, and she also had vivid memories of that time in Birmingham when a bomb ripped through the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church and when nonviolent groups were met with water hoses and snarling dogs. Plus, she was a teacher at historic Ullman High School during the civil rights movement in Birmingham. Woolfolk knew instantly that she wanted to be a part of creating such a monument in the city.

Old Wounds

Those years of steering the task force were difficult, Woolfolk recalled. It was a challenge to convince so many people that the institute was necessary for the education of a new generation of children who had not witnessed what happened.

“People just wanted to forget the pain of that time,” she said.

Arrington agreed with Woolfolk.

“No one wanted to open old wounds,” he said, pointing out some in the business community, whom felt the BCRI would be only for black patrons and, worse, cause a backlash against whites in the city.

Blacks had reservations about the project, too, because they didn’t trust the city to get the story right.

Nonetheless, the city’s history had to be told—openly and honestly. Members of the original task force, including Dr. Ed LaMonte, a retired Birmingham Southern College political science professor, and Dr. Robert G. Corley, a professor in the Department of History at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), said the BCRI had to address some uncomfortable subjects.

“I remembered the [Sixteenth Street Baptist] church bombing,” said Corley, who grew up in Birmingham and served as the Regional Director of the National Conference of Christians and Jews (NCCJ). “I was [five years old] when the demonstrations happened, and at the time I was trying to figure out my values and how I fit into the world.”

“I was very eager to be a part of it,” Corley continued. “We wanted it to be not just a museum but an institute where there is an ongoing discussion. We also needed something that could educate children here about what really happened.”

Funding

Arrington placed two different bond issues before voters in Birmingham: one that included revenue for schools, recreation, and public works; and another to fund a civil rights museum. Both times, items involving the museum failed. Arrington persisted and was able to generate the $12 million necessary to build the institute, but he still encountered continued resistance from Birmingham’s corporate community. However, when the business leaders had the opportunity to view plans for the new facility, along with the storyline planned for the exhibition, they eventually came to understand the potential and offered their full backing, raising another $5 million to complete the exhibition and provide financial support through the first several years of operation.

Woolfolk also continued to push forward, and eventually the task force made decisions on the design and exhibitions. She especially wanted to give credit to Birmingham’s foot soldiers, those residents who were on the front lines of and made a huge difference during the city’s demonstrations.

Doors Opened

After eight years of planning, the doors of the 28,000-plus-square-foot building opened in 1992—with many who had been opposed now onboard. Woolfolk noted that those same business leaders that were hesitant to support the institute had come around and were investing in it.

“When there was something to look at, we got more support,” she said.

When the BCRI opened, it was one of the few institutions that focused on the civil rights movement, said Lawrence J. Pijeaux Jr., EdD, who served as BCRI president and CEO from 1995 to 2014.

“It was just us and the [National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, Tenn.], which opened a year earlier,” he said. “We attempted to help each other.”

Now, according to the Association of African-American Museums, there are more than a dozen museums and institutions that chronicle the civil rights movement, including the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., which opened in 2016, and the Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta, established 10 years ago.

The BCRI, now an affiliate of the Smithsonian Institution, has grown into a cultural and educational research center that promotes a comprehensive understanding for the significance of civil rights developments in Birmingham. It reaches more than 150,000 individuals each year through its award-winning programs and services.

Renowned as a model for other museums that chronicle social-change movements, the BCRI was recognized by two White House administrations for its educational efforts and was also awarded money to train African-American museum professionals, Pijeaux said.

“There have been so many positive things to come out of the institute,” he said. “And its future is bright.”

National Monument

Earlier this year President Barack Obama established the Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument, which includes the BCRI, along with the Birmingham’s Civil Rights district, where the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, Kelly Ingram Park, the A.G. Gaston Motel, and Bethel Baptist Church are located. The designation has prompted the BCRI to go through an in-depth strategic-planning process, and the institute’s leaders hope more visitors will be drawn to the facility.

“We have almost immediately begun to shift into a different gear,” said BCRI president and CEO Taylor. “For example, we are looking to double the number of visitors by 2020. We are looking at how are we can take full advantage of all the attractions within the National Monument designation, and how we can be relevant and meaningful.”

“The designation has reaffirmed for us the importance of the BCRI and how important Birmingham is to national history,” she said. “I am very heartened by the interest and even larger role we might play in sharing that history.”