By Ameera Steward

The Birmingham Times

Not far from the main campus of Tuskegee University are four large barns that house horses, cows, goats, sheep, pigs—“common farm-animal species”—awaiting checkups and exams. The barn is about a 10-minute walk from a small animal hospital that provides emergency and critical care, dentistry, surgery, and other veterinary services. Outside the barn, slightly up the hill, stretch approximately 40 acres of pastureland for horses and cattle.

Welcome to the Tuskegee University College of Veterinary Medicine (TUCVM), the only veterinary medical professional program located on the campus of a Historically Black College or University (HBCU). The TUCVM has educated about 70 percent of African-American veterinarians and is recognized as the most diverse of all 30 institutions of veterinary medicine in the nation. Its students, who hail from the U.S. and several other countries, form a bond unlike any other.

“When I was here on the day of the interview [for vet school], it was like being welcomed to your family’s living room,” said Kaitlynn Pfeiffer, a first-year TUCVM student from Syracuse, N.Y. “It was just a very family-friendly atmosphere and somewhere you knew you would be able to thrive as a student.”

Notable Alums

Alums can be found serving in prominent positions throughout the U.S.—and in Birmingham, too. At Southern Research, a nonprofit research organization, Sheila D. Grimes, PhD, DVM, serves as an anatomic pathologist and oversees a team of pathology, histology, necropsy, and clinical pathology personnel. A veterinary pathologist with more than 30 years of experience, Grimes earned her Doctor of Veterinary Medicine (DVM) and Bachelor of Science (BS) degrees from Tuskegee.

“We are proud to see professionals of all colors and from walks of life being served so well by a Tuskegee University degree throughout their veterinary careers,” said Tuskegee University President, Lily D. McNair, PhD, who was inaugurated last week as the first woman to serve in that position for the institution.

To get a closer look at Tuskegee’s top-notch veterinary medicine program, the Birmingham Times recently spent a day on the Montgomery-based campus, visiting the barns, viewing the animals, and speaking with administrators, faculty, and students.

Animal Barns

The Palpation Barn on the Tuskegee campus is an enclosed, self-contained facility, where veterinary students learn how to examine horses to evaluate the animals’ reproductive and gastrointestinal systems. Nearby are the Hay Barn, Equine Barn, and Food Animal Barn. Under the care of TUCVM students, the horses live pretty good lives at the university, said Elizabeth Yorke, DVM, Section Head for Large Animal Medicine and Surgery.

The animals are fed and get regular checkups from students who gauge vital signs like temperature, pulse, and respiration.

“Overall, [we] check with the horse’s body condition, see if he’s in good weight. … [We listen] to the lungs, … the heart, … evaluating the same parameters we would if you were checking your own pulse right after a run,” Yorke said. “Most of the horses were [show horses] or developed … leg injuries and [couldn’t] be ridden anymore. They’re nice, gentle horses, so they were donated to the university, and we just keep them.”

Students spend a few weeks at a time in the Equine Barn before going out to the large-animal ambulatory facility: “They drive out with faculty to farms [to] see cattle, goats, and horses,” Yorke said. “They go to the clients as opposed to the clients coming here to the barn.”

In addition to the horse barn, the TUCVM has a Food Animal Barn, which houses cattle in need of treatment. The institution also has a herd of goats.

“We do a little bit of everything,” Yorke said.

Animal Hospitals

The small-animal hospital consists of wards for cats, dogs, and “pocket pets” (hedge hogs, guinea pigs, snakes, lizards, etc.) that include treatment areas, an intensive care unit (ICU), and surgery suites. The facility provides emergency and critical care, as well as dentistry, internal medicine, outpatient services, soft-tissue surgery, orthopedics, neurosurgery, and ophthalmology.

Sometimes clients bring animals to the hospital, and sometimes one of the vets plus the students go out to farms, said Yorke: “That’s our ‘ambulatory rotation.’ … [Students] spend two or three weeks here in the hospital, and then they spend a few weeks with vets, driving to farm calls.”

Mostly juniors and seniors are taught in the animal hospitals: “[The] first year is a lot of book work with an introduction to clinicals. The second year is book work with a little bit more introduction to clinicals. The third year is half and half. The fourth year [involves] clinical rotation,” said LaTia McCurdy, TUCVM Director of Veterinary Admissions and Recruitment.

Rotations and Radiology

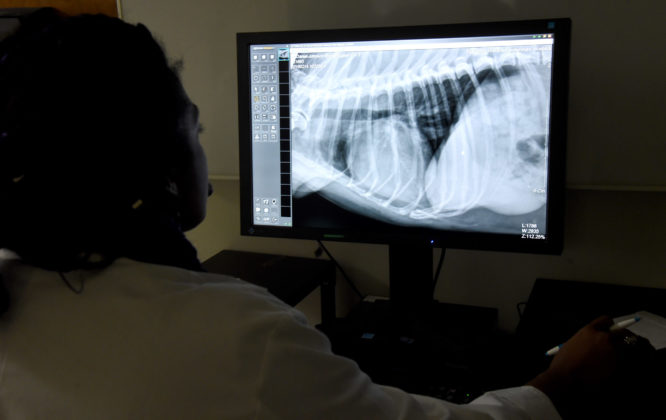

Students receive training via large-animal and small-animal rotations. They also learn specialty services, such as radiology.

“Students get a very wide range of training on all the disciplines,” said Yorke. “Then they can decide from there [whether] they want to specialize in one or … be a generalist and mixed-animal practitioner, working on horses, dogs, and cats.”

Students spend a lot of their time in the radiology viewing area doing diagnostics.

“Often, X-rays are a part of those diagnostics, so this is where students … make interpretations of the X-rays and talk through things,” said Pamela Martin, DVM, Head of the Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences.

TUCVM students also get the opportunity to compare previous and recent X-rays of returning patients. When they see patients, Martin said, students are conducting practice examinations and learning skills they’re expected to know as graduates. After assessing a patient, students develop a plan.

“We either agree to their plan or enhance their plan, … then we go through the diagnostic processes,” said Martin. “[Faculty members] either observe them as they perform minor skills or are directly involved in some of the diagnostic work. Faculty are directly involved if it’s more of a specialty type of activity or something that requires advanced training, but we want our students to get a lot of hands-on experience, so they’re able to [handle these tasks] in practice after they graduate.”

Students spend a little more time with internal medicine services “because our patients can be [either acutely or chronically] ill; … they may spend 10 to 12 hours here on a daily basis for the time they’re on their rotation,” Martin said, adding that other rotations may require four or five hours a day, depending on the service.

Once a year in the spring, Tuskegee hosts an animal health fair, “which offers discounted services for vaccines, deworming, and physical exams. It’s a full day for anyone who wants to bring their animal for some services that are discounted on that day,” Martin said.

Primary Mission

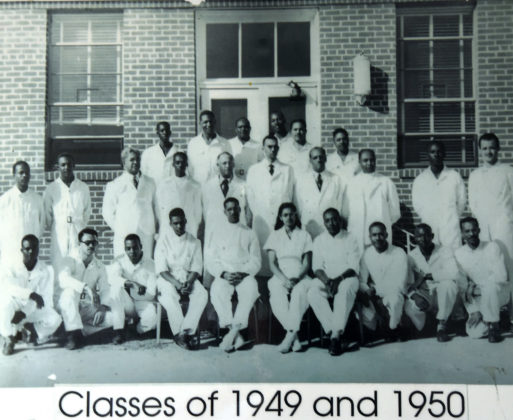

The TUCVM was established in 1945 to educate African-Americans during the time of segregation. When the program started, there were fewer than five black veterinarians practicing in the South; it was formed because black farmers were unable to find veterinarians to take care of their farm animals.

The primary mission of the TUCVM is to provide an environment that fosters a spirit of intellectual curiosity, creativity, critical thinking, problem-solving, and leadership that promotes teaching, research, and service in veterinary medicine and related disciplines—and that mission has not changed, said TUCVM Dean and Professor of Radiology Ruby L. Perry, DVM.

“We’re [concerned about] animal welfare. You can see that in the kind of research we do, the kind of disciplines,” she said. “Who would think [about having] … a person board-certified in equine surgery, … equine medicine, small-animal medicine, small-animal surgery, dentistry? We have to make tough decisions. We have to do problem solving. We have to do critical thinking. … We’re doctors. … We … have to look at the [the animal’s] behavior, the signs, then we have to come up with a diagnosis.”

“Tuskegee Experience”

The veterinary medicine programs at Tuskegee align with the university’s rich tradition of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education, McNair said.

“This certainly is demonstrated by how many of our students and faculty benefit from cross-disciplinary studies and research between the college and other science-focused programs, such as agriculture, animal sciences, biology, and food safety and security,” she said.

Faculty members also know firsthand the benefits of a Tuskegee education. Perry, for instance, is an alum who returned to the institution to make a difference and be a trailblazer, a value that is inspired in every Tuskegee University student.

“That’s just instilled in us. … Somebody gave you an opportunity, and you share that with somebody else, and when you leave you share that with somebody else,” Perry said. “That’s what we refer to as that ‘Tuskegee Experience.’”

Click here to read more stories on TUCVM: At 40, Russell Johnson’s wish for a vertinary doctorate from Tuskegee about to come true.