By Tom Hagler

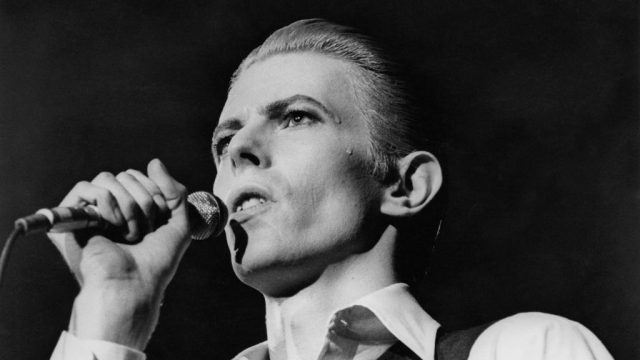

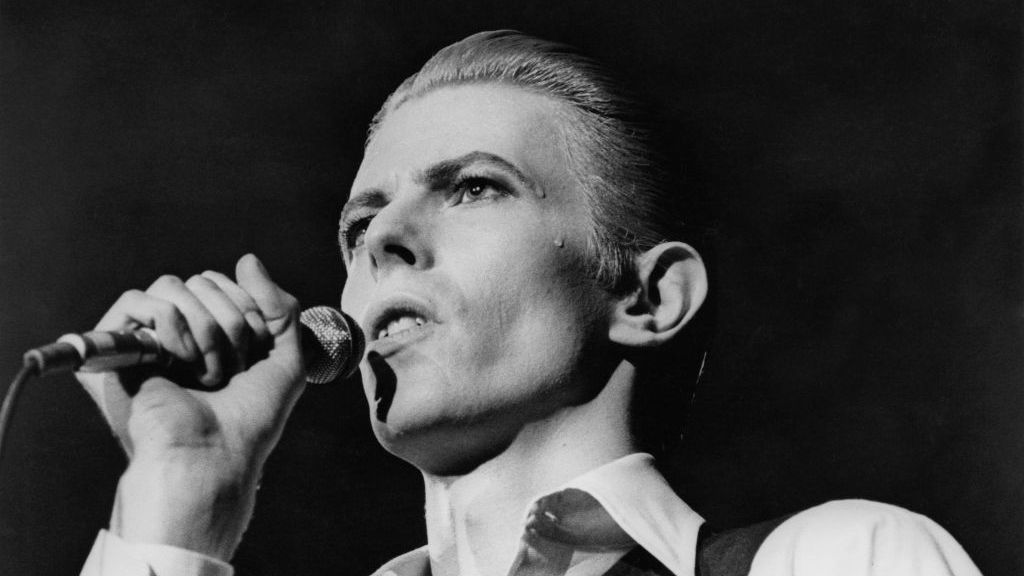

From mime artist to Buddhist monk, David Bowie made several left-field changes in his career.

One occurred in the mid-nineties when he became a journalist after offering the art world the unobtainable — an interview with the “least known great painter of the 20th Century.”

But in four hours of conversation, the singer never once asked the elderly Balthus about the most notable aspect of the painter’s work: the allegations of pedophilia.

A new book on Bowie looks back at the singer’s meeting with the 86-year-old Polish-French artist, and tries to understand why Bowie steered away from the most notable feature of his interviewee’s art.

Balthus was the last survivor of the School of Paris, a group of diverse, innovative artists, including Picasso, Matisse, Chagall, Mondrian and Modigliani, who rejected established artistic practices. But while his contemporaries embraced new styles, Balthus’ main challenge was in his content; paintings of pre-pubescent girls in a series of erotic and voyeuristic poses.

Bowie had recently bumped into the artist’s wife at an exhibition in Switzerland and discovered they were almost neighbors. Telephone numbers were exchanged and Bowie called her husband suggesting a meeting.

“Shall I bring a ‘proper’ journalist,” Bowie asked. “Good heavens, no,” replied Balthus. “I can’t stand art journalists. They are always so intellectual. I’d prefer you to do it, dear boy.”

Bowie almost did not make it to the painter’s chalet. “I was so petrified, I nearly turned back three times,” he said. Not only would this be his first “serious” article in a “serious” publication, it would also define whether he would sink or swim in the new world of high art and intellectualism.

“I wanted to show my mettle,” Bowie said, who had just joined the board of Modern Painters. “Being a rock singer — Rock GOD — it’s quite hard to convince people that your interests extend outside the parameters of purely being up on stage wearing funny trousers.”

The two men hit it off from the start and the resulting 20 pages was the longest interview the magazine ever printed.

“That was a joy to do because he was such a gentleman and so mysterious and knew he was pulling you into his myth,” recalled Bowie. Balthus spoke about lunching with Marlon Brando. Picasso, he said, had defended him when the Polish painter was accused of being a fascist for painting figurative art. “He knew ’em all,” Bowie told Raygun magazine. “Hung out with Pablo, got drunk with Duran and all the rest of it. And it was great sort of having him go back and then suddenly remember. [elderly voice] ‘Oh. I remember Pablo would say to me…’ or ‘I was sitting there with Igor…’ Stravinsky!”

Balthus also mentioned how the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke, his mother’s lover, had helped him as a young boy publish his first book at the age of 11.

The painter appeared unaware of Bowie’s side job as a rock god. “Are you used to photographers?” he asked innocently, as a cameraman took snaps of the two. “Unfortunately, yes,” replied Bowie.

“There were so many secrets about him,” Bowie later said, although the most notable “secret” — the allegations of pedophilia — was scarcely touched upon. Paintings of pre-pubescent girls in provocative poses, allied with allegations of affairs with his young “models”, had swirled around the painter since the 1930s. Therese with Cat (1937) and Therese Dreaming (1938) both show a girl leaning back on a chair with one leg raised to expose her white knickers. Balthus would tell interviewers, years later, that this is simply the way young girls sit. The Street (1933) is more explicit with, at one end of the canvas, a man apparently groping a girl, who maintains a blank expression.

A 1938 painting was used by Penguin as the cover of Nabakov’s Lolita. According to art critic John McDonald, Balthus took up with at least two of his models when they were teens, although the exact age when the affairs began is debated. “Today, it seems no less amazing that Balthus could deny his predilection for young girls than Liberace could sue people for claiming he was gay,” McDonald wrote in the Sydney morning Herald.

Eventually, a museum in Germany would ban his work, others would face petitions to do the same, the New York Times refused to reprint his paintings, and Tracey Emin was not alone in the artistic community for labeling the painter “a pervert.”

But when speaking to Bowie, Balthus was to bring up the issue himself by mentioning one of his most controversial paintings. “The Guitar Lesson” features a young girl, skirt pulled up and naked from the waist down, lying on the lap of a female music teacher whose pulled-down blouse reveals an aroused nipple.

“I was in bad shape and I wanted to make a name for myself,” Balthus told Bowie. “You know, David, in these days, the only way to make a name for oneself was to scandalize.”

Rather than point out that Balthus had continued to paint explicit images of pre-pubescent girls even after attracting notoriety and fame, Bowie replied: “Provocation has paved the way and fostered the careers of many.”

Unprompted, almost as if he needed to get something off his chest, Balthus went on, “I am simply attracted to the immature forms of a teenager, that is all.” Again, Bowie declined to take up the offer to delve into that most talked-about aspect of the artist’s career, as any trained journalist would surely have, and instead seemingly went off on a tangent to ask about the artist’s symbolic use of books and mirrors.

Maybe Bowie thought the allegations of pedophilia were spurious, or that “the work” was more important than the life, or that a challenge from a rock star might feel hypocritical.

Or maybe Bowie sympathized with the view of Bono, who was such a fan of the artist he sang at Balthus’ funeral. “In Balthus’ era, the only subject you couldn’t approach with any curiosity was puberty,” the Irish singer told French journalist Michka Assayas. “You weren’t allowed to go there, so he had to go there. For me and rock ‘n’ roll, it was spirituality. You just can’t go there, so I had to go there.”

The singer was delighted with the interview and its impact: “I see it now quoted in academic things saying, ‘From the Bowie interview’. Whoa, that’s me!”

“As with any aged gentleman that I come into contact with, my immediate need is to treat him as the grandfather I never knew or the father I needed more of,” Bowie told The Independent’s David Lister. “We are time and worlds apart, which has made for a rather lovely friendship.”

As for courting controversy, or perhaps skirting controversy in the case of the interview itself, Bowie concluded that he and Balthus were both prepared to shock to pursue their beliefs or, as the singer termed their mutual philosophy, “Put it out and be damned.”

Tom Hagler is the author of “We Could Be: Bowie and his Heroes,” which tells the history of Bowie through short stories of his encounters with fellow icons.

Edited by Kristen Butler

The post All The Wrong News: How Bowie Flopped As A Reporter appeared first on Zenger News.